20 Classification

20.1 Logistic Regression

Goal: Predict a 1

- Response: 0 or 1

- Predictions: probability of a 1?

Why Not Linear Regression?

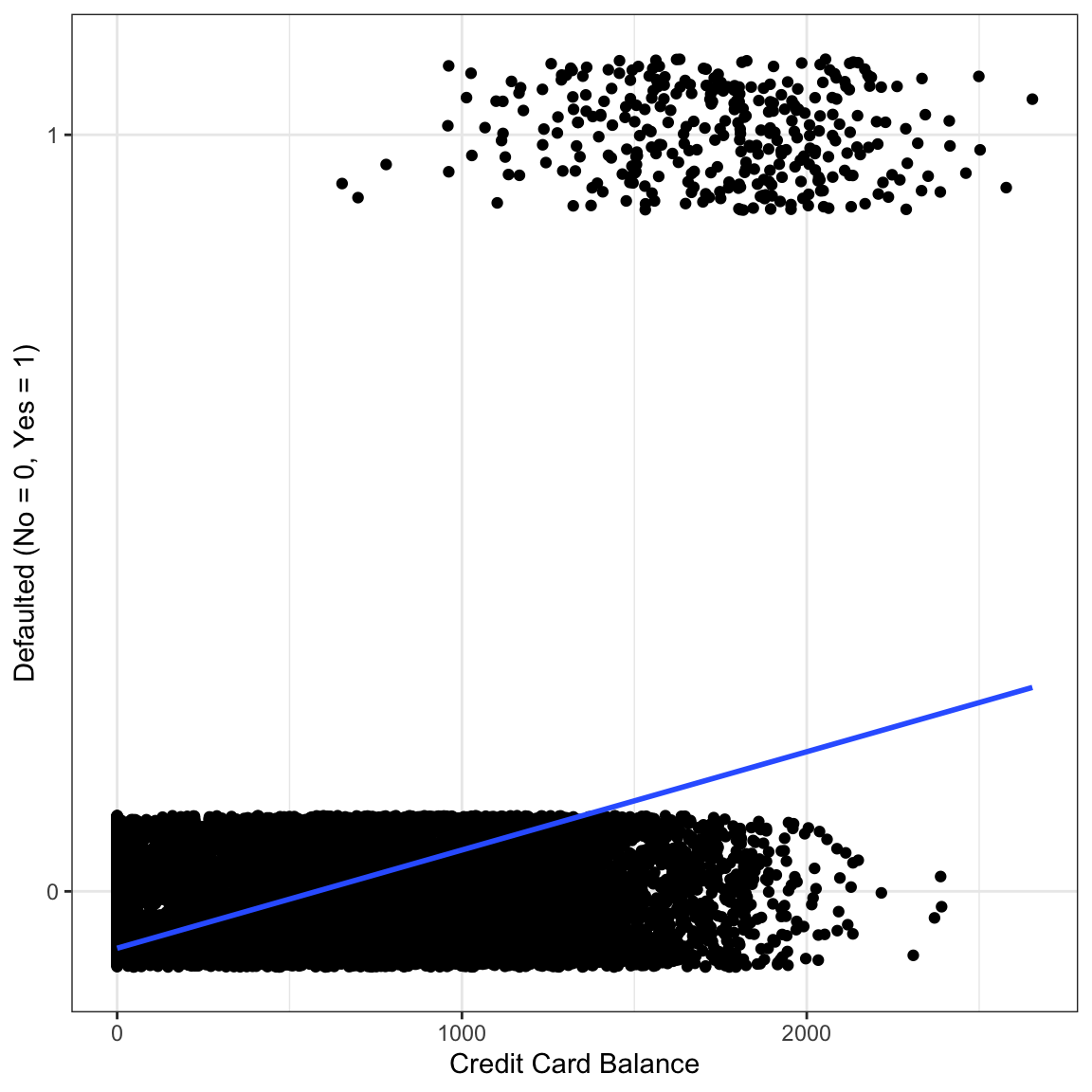

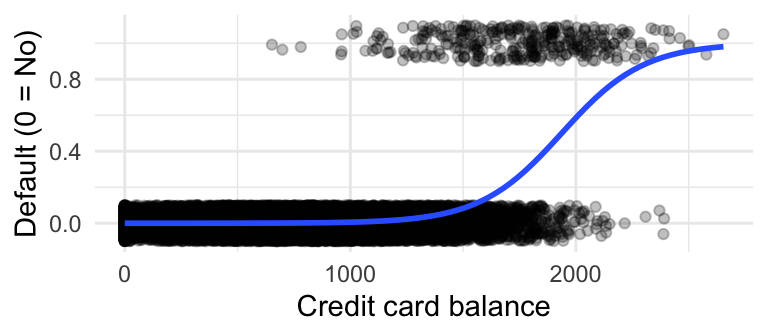

The plot on the right shows Default versus Credit Card Balance (with jittering).

- “Default” is 0 for No, 1 for Yes

- Dummy encoding for the response

- Linear model predicts negative values!

- Also, values above 1.

- What could the slope possibly represent???

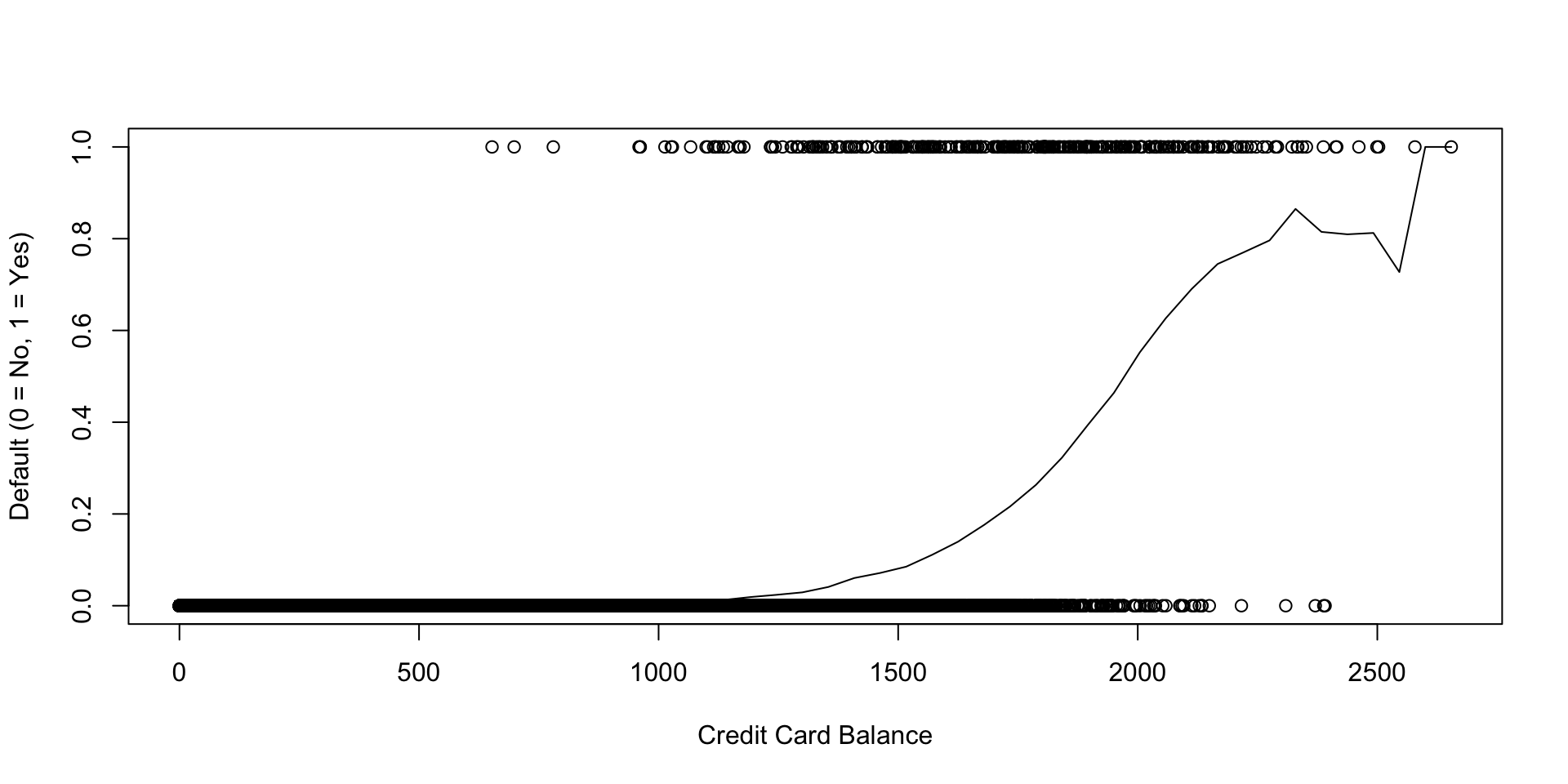

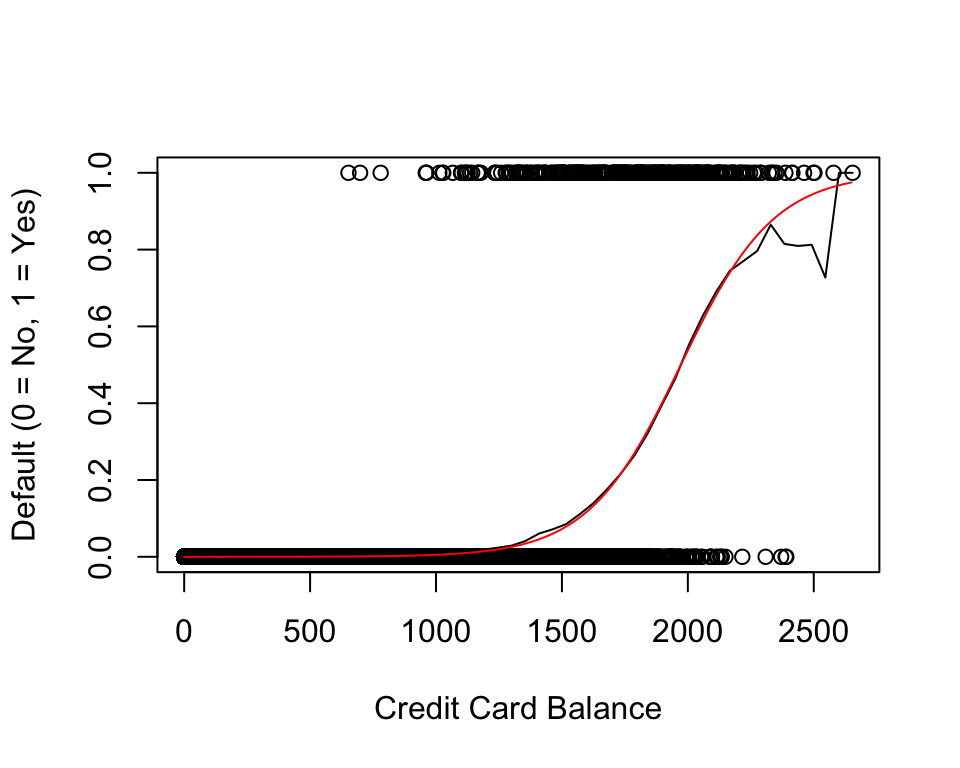

The mean of y at each value of x

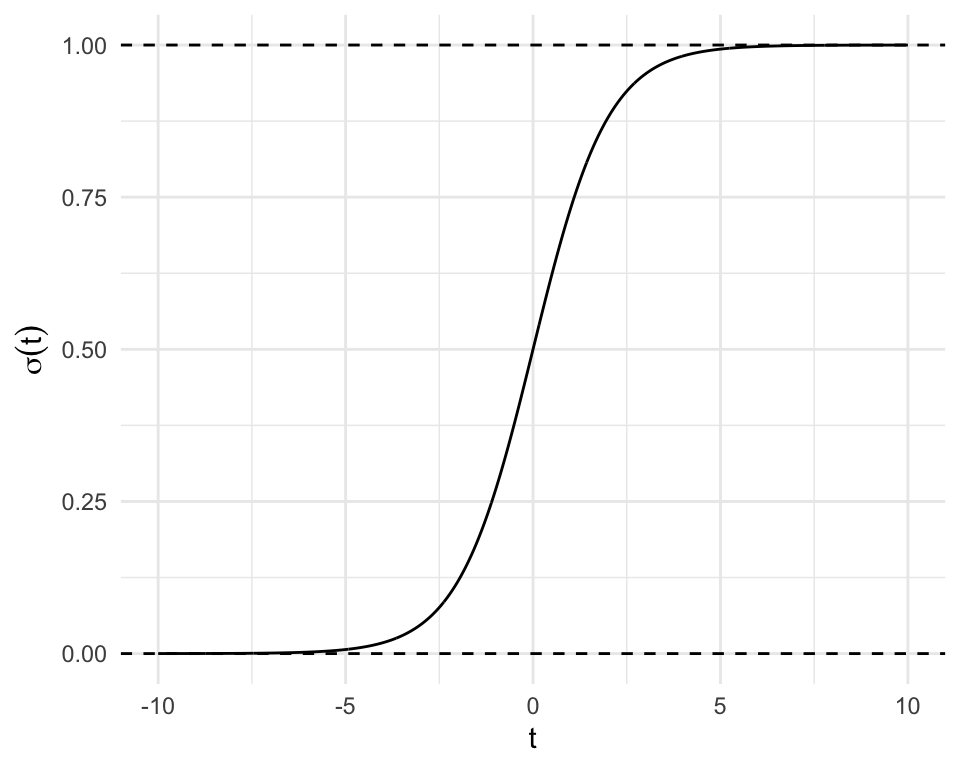

The Logistic Function - A Sigmoid

If \(t\in\mathbb{R}\), then \[ \sigma(t) = \dfrac{\exp(t)}{1 + \exp(t)}\in[0,1] \] where \(\sigma(\cdot)\) is the logistic function.

Logistic Function - Now with Parameters

\[ \sigma(\beta_0 + \beta_1 t) \]

#| standalone: true

#| viewerHeight: 600

#| viewerWidth: 800

xseq <- seq(-10, 10, 0.05)

sigma <- function(t) exp(t)/(1 + exp(t))

input <- list(b0 = 0, b1 = 1)

ui <- fluidPage(

sidebarPanel(

sliderInput("b0", "Intercept B_0", -5, 5, 0, 0.1, animate = list(interval = 100)),

sliderInput("b1", "Slope B_1", -5, 5, 1, 0.1, animate = list(interval = 100))

),

mainPanel(plotOutput("plot"), )

)

server <- function(input, output) {

output$plot <- renderPlot({

yseq <- sigma(input$b0 + input$b1 * xseq)

plot(yseq ~ xseq,

xlim = c(-10, 10),

ylim = c(0, 1),

ylab = bquote(sigma (beta[0] *" + " * beta[1] * t)),

xlab = "t",

type = "l")

})

}

shinyApp(ui = ui, server = server)Logistic Function - Now with Parameters Estimated from DATA

\[\begin{align*} \eta(x_i) &= X\underline{\beta}\\ p_i &= \sigma(\eta(x_i))\\ \implies \log\left(\frac{p_i}{1-p_i}\right) &= X\underline{\beta} \end{align*}\]

\(\eta(x_i) = -10.65 + 0.0054\cdot\text{balance}_i\)

Logistic Regression

- The response is 0 or 1 (no or yes, don’t default or default, etc.)

- The probability of a 1 increases according to the sigmoid function.

- The linear predictor is \(\eta(x_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_{i1} + \beta_2x_{i2} + \cdots\)

- The probability of class 1 is \(P(\text{class }1 | \text{predictors}) = \sigma(\eta(x_i))\)

- Instead of normality assumptions, we use a binomial distribution.

It’s just one step away from a linear model!

Interpreting Slope Parameters

- General structure: “For each one unit increase in \(x_i\), some function of \(y_i\) changes by some function of \(\beta\)”.

- For logistic regression:

- One unit increase in \(x_i\), \(\log\left(\frac{p(x_i)}{1-p(x_i)}\right)\) increases by \(\beta\).

- The odds are \(\frac{p(x_i)}{1-p(x_i)}\).

- “1 in 5 people with odds of 1/4 will default.”

- \(\beta\) is the change in log odds for a one unit increase.

- “log odds ratio”.

Odds Ratios

Consider the one-predictor example.

\[ \eta(x_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_{i1}\text{ and }\eta(x_i + 1) = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \beta_1\text{, }\therefore \eta(x_i + 1) - \eta(x_i) = \beta \]

The logg odds ratio is defined as \[ \log(OR) = \log\left( \frac{p(x_i + 1)}{1 - p(x_i + 1)} \middle/ \frac{p(x_i)}{1 - p(x_i)}\right) \] Using \(\eta(x_i) = \log\left(\frac{p(x_i)}{1-p(x_i)}\right)\), show that \(\log(OR) = \beta_1\)

The Loss Function

For all observations:

- If \(y_i = 0\), we want \(p(x_i)\) to be as low as possible.

- Maximize \(1 - P(Y_{i} = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X)\)

- If \(y_i = 1\), we want \(p(x_i)\) to be as high as possible.

- Maximize \(P(Y_{i} = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X)\)

These can be combined as: \[ \prod_{i:y_{i} = 0}\left(1 - P(Y_{i} = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X)\right)\prod_{i:y_i=1}P(Y_i = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X) \] which is equivalent to: \[ \prod_{i=1}^n(1 - P(Y_{i} = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X))^{1 - Y_i}P(Y_i = 1|\beta_0,\beta_1,X)^{Y_i} \]

Which is NOT just the sum of squared errors!

Unlike linear regression, there’s no closed form for \(\hat{\beta}_0\) and \(\hat\beta_1\); we need numerical methods.

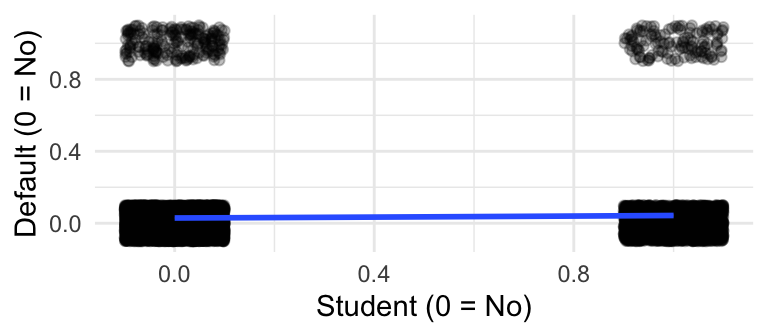

Examples: Two different predictors in the Default data

\[ \eta(x_i) = -3.5 + 0.5\cdot\text{student} \]

Odds of a student defaulting are \(\exp(0.5)\approx1.65\) times as high as a non-student.

\[ \eta(x_i) = -10.65 + 0.005\cdot\text{balance} \]

Each extra dollar of CC balance increases odds of defaulting by a factor of 1.005.

The scale of the predictors matters.

Odds versus Probabilities

“The odds of a student defaulting are \(\exp(0.5)\approx1.65\) times as high as a non-student.”

\[ \frac{P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 1)}{1 - P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 1)} \biggm/ \frac{P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 0)}{1 - P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 0)} = 1.65 \]

This cannot be solved for \(P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 1)\)!

\[ P(\text{default} | \text{student} = 1) = \dfrac{\exp(\eta(x_i))}{1 + \exp(\eta(x_i))} \approx 0.047 \]

Multiple Linear Logistic Regression

- Predictors can be multicollinear, confounded, and have interactions.

- Logistic is just Linear on a transformed scale!

- We do not look for transformations of the response.

- It’s already a transformation of the response \(p_i(x_i)\)!

- We do look for transformations of the predictors!

- Sigmoid + Polynomial is where the real fun is.

Errors in Logistic Regression: Deviance

- All “errors” are either \(p(x_i)\) or \(1 - p(x_i)\).

- i.e., distances are measured form either 0 or 1.

Instead, we use the deviance.

- If \(p(x_i)\) were the true probability in a binomial distribution, what’s the probability of the observed value (0 or 1)?

- In other words, \(P(Y_i = 1| \beta_0, \beta_1, X)\) and \(1 - P(Y_i = 1| \beta_0, \beta_1, X)\) are the residuals!

- The residual we use depends on what the response is. If \(y_i = 0\), the residual is \(P(Y_i = 1 | \beta_0, \beta_1, X)\)

- This is used more broadly in Generalized Linear Models (GLMs). Logistic Regression is one of many GLMs.

- In other words, \(P(Y_i = 1| \beta_0, \beta_1, X)\) and \(1 - P(Y_i = 1| \beta_0, \beta_1, X)\) are the residuals!

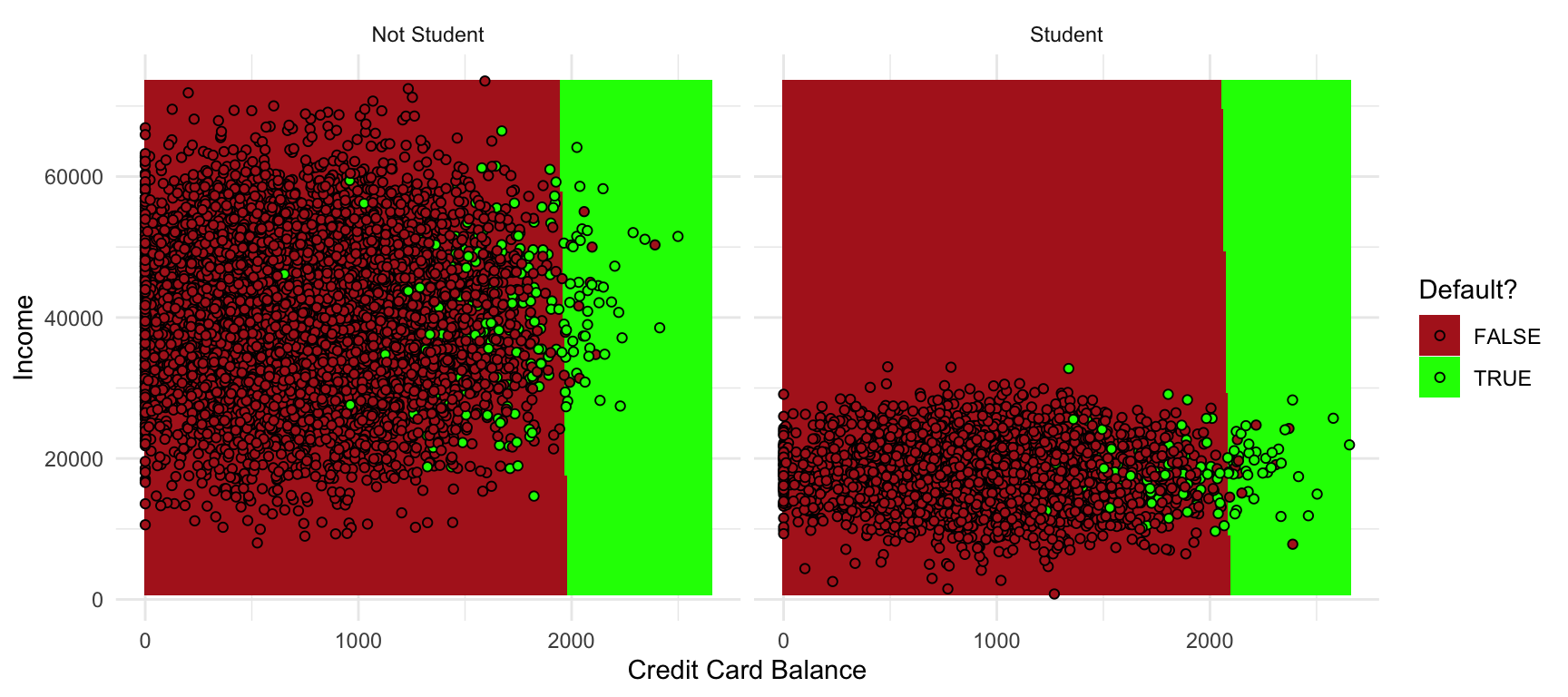

Logistic Decision Boundaries

\[ P(\text{defaulting} | \eta(x_i)) > p \implies a + bx_1 + cx_2 + dx_3 > e \]

for some (linear) hyperplane \(a + bx_1 + cx_2 + dx_3\) and some value \(e\).

- Choosing \(p=0.5\) is standard, but other thresholds can be chosen.

- Cancer example: want to be more admissive of false positives

- Would rather operate and be wrong than falsely tell the patient that they’re healthy!

- Cancer example: want to be more admissive of false positives

Predictions - Just Plug it In!

| Intercept | Student | Balance | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\beta\) | -10.09 | -0.65 | 0.0057 | 0.000003 |

We can make a prediction for a student with $2,000 balance and $20,000 income: \[\begin{align*} \eta(x) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1\cdot 1 + \beta_2\cdot 2000 + \beta_3\cdot 20000 \approx 0.0178\\ &\\ P(\text{defaulting} | x) &= \dfrac{\exp(\eta(x))}{1 + \exp(\eta(x))} \approx \dfrac{\exp(0.0178)}{1 + \exp(0.0178)} \approx 0.504\\ &\\ &P(\text{defaulting} | x) > 0.5 \implies \text{Predict Default} \end{align*}\]

Standard Errors: It’s complicated

We don’t have an estimate like \(\hat\beta = (X^TX)^{-1}X^TY\). We had to resort to numerical methods.

There is a closed form for \(V(\hat\beta)\) and a way to test significance, but they’re beyond the scope of this course.

- Relies on likelihoods, which we avoided in this course.

- You can assume significance tests in R output are correct.

20.2 Classification Basics

Goal: Predict a Category

- Binary: Yes/no, success/failure, etc.

- Categorical: 2 or more categories.

- A.k.a. qualitative, but that’s a social science word.

In both: predict whether an observation is in category \(j\) given its predictors. \[ P(Y_i = j| x = x_i) \stackrel{def}{=} p_j(x_i) \]

Classification Confusion

Confusion Matrix: A tabular summary of classification errors.

| True Pay (\(\cdot 0\)) | True Def (\(\cdot 1\)) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pred Pay (\(0 \cdot\)) | Good (00) | Bad (01) |

| Pred Def (\(1 \cdot\)) | Bad (10) | Good (11) |

- Two ways to be wrong

- Two ways to be right

- Different applications have different needs

Accuracy: \(\dfrac{\text{Correct Predictions}}{\text{Number of Predictions}} =\frac{00 + 11}{00 + 01 + 10 + 11}\)

Is “Accuracy” Good?

Task: Predict whether a person has cancer

(In this made up example, 0.02% of people have cancer).

| True Healthy | True Cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| Pred. Healthy | Save a Life | Lose a Life |

| Pred. Cancer | Expensive/Invasive | All good |

- Easy: 99.8% accuracy.

- Always guess “Not Cancer”

- Very Hard: 99.82% accuracy.

The Confusion Matrix for Default Data

| True Payment | True Default | |

|---|---|---|

| Pred Payment | 9627 | 228 |

| Pred Default | 40 | 105 |

- This model: 97.32% accuracy.

- Naive model: always predict “Pay” - 96.67% accuracy!

Other important measures (not on exam):

- Sensitivity: \(\dfrac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{All Positives in Data}} = \dfrac{9627}{9627 + 40} = 99.58%\) (Naive: 100%)

- Specificity: \(\dfrac{\text{True Negatives}}{\text{All Negatives in Data}} = \dfrac{105}{105 + 228} = 31.53\) (Naive: 0%)

Logistic Regression in R

The residual plots are the same as before:

The predictions can either be on the logit scale (type = "link", the default) or on the response scale (probabilities).

Regularization is often used with logistic regression (in python’s scikit-learn package, Ridge regularization is used by default without warning the user).